Introduction

When I love a game, I try to learn as much about it as I possibly can. One of the things I find most fascinating about many of the games I play is how they change in their respective localizations. I really enjoy examining the text, graphics, and minute details in the Japanese versions and comparing them to their English counterparts. I love seeing how the localization team attempts to adapt a piece of media and judging how well they manage to transfer the original message. I also enjoy trying to get into the developers' and localization teams' heads to understand why and how something was changed. That's why I've always been a big fan of Clyde Mandelin's Legends of Localization website and have even bought some of his books.

One of my favorite games is Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon, and up until recently, it was the only Archanean FE game to be localized into English. Naturally, I wanted to learn more about how different FE11 was in English compared to its Japanese counterpart and other languages. While there are some wiki pages and sites like The Cutting Room Floor that list localization changes, there were no dedicated articles that compiled everything and discussed these changes in depth. That’s why I’m here today to share this blog post where I list and discuss many of the localization changes in FE11, in the same style as Clyde Mandelin's Legends of Localization series

Humble Beginnings on the Famicom

Before talking about Shadow Dragon, I want to give more background by discussing the game it was a remake of, Fire Emblem Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light (FE1), as well as the other remake, Fire Emblem Mystery of the Emblem (FE3).

Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light is the first game in the Fire Emblem series and originated as a doujin project called Battle Fantasy - Fire Emblem. It was brainstormed by Shouzou Kaga, who had worked at Intelligent Systems up until the release of the fifth Fire Emblem game, and in the previous year achieved third place in Enterbrain's LOGiN magazine game coding contest with his entry titled Cosmic Fighter, described as a "role-playing game with hidden romance elements."

The idea for "Fire Emblem" came into existence in 1987 after the completion of Famicom Wars. Intelligent Systems wanted to move away from the military wartime setting presented in Famicom Wars and shift towards a more traditional fantasy-type RPG game in the same vein as Dragon Quest or Final Fantasy.

However, this game wouldn't be a standard JRPG. In addition to JRPGs, Kaga was also a big fan of strategy games but felt that, at the time, many of them were just about clearing an objective and didn't have room for the player to empathize with the characters and story, as many JRPGs did. Conversely, Kaga felt that one of the drawbacks of JRPGs was that there was always just a single protagonist. So, players could only experience a linear story that the game designer had prepared for them.

With these criticisms in mind, Kaga prepared a design document for a game called Fire Emblem, a game in which he took aspects from these two genres that he enjoyed. It outlined game mechanics, map scenarios, and character information, among other things. The concept of the game was highly ambitious at the time, leading to the necessity of cutting, removing, or scaling back various elements. The most discussed setback was related to the graphics, which became the major criticism of the game in Japan. However, despite facing challenges, the game was eventually released with some assistance from some higher-ups at Nintendo.

An important note is that FE1 not only marked the inception of the Fire Emblem franchise but also essentially pioneered its genre. While other games attempted to blend strategy games with RPGs, they were mainly limited to tactical-based random encounters or leaned closer to action-adventure games.

This point is worth highlighting because Japanese fans initially criticized the game as being "too complex" or "hard to understand" simply due to the lack of similar games in the market. However, as people began to comprehend the game, and word of mouth spread, FE1 became a hit in Japan. Shouzou Kaga, the creator, was promoted to head designer for future Fire Emblem games. Moreover, Fire Emblem's unique gameplay served as inspiration for many other games that either emulated or built upon FE1's initial design. And while the people within the English community may vehemently disagree, FE1 definitely had a large impact.

Transitioning to the 16bit World

A few years later, after the release of the second game, Fire Emblem Gaiden, the team went to work to develop Fire Emblem: Mystery of the Emblem. Initially conceived as solely a sequel to the first game, discussion would lead to the additional inclusion of a remake of the original game for people who hadn't played it. This version of Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light would include a few changes like the removal of some chapters and characters, some altered dialogue, a change in the battle system, and obvious graphical and music upgrades as they were now working with a fancy-schmancy 24 megabit cartridge.

And to put things bluntly, FE3 was a commercial success. FE1 got people to notice Fire Emblem, but FE3 was the game that put the series on the map for most Japanese players, cementing it as one of Nintendo's more notable IPs in the same tier as games like Mother, F-Zero, and Pikmin. With that said, FE3 would end up being the best-selling game in the series before Awakening in 2012. FE3's popularity would further spawn an OVA, a manga, and numerous pieces of merchandise, and served as a justification for including the poster boy, Marth, in the Super Smash Bros. series of games.

Recapturing the Original's Glory

Fast forward to 2007, and we have Fire Emblem Shadow Dragon, which started development during the development of Fire Emblem Radiant Dawn. Intelligent Systems wanted a chance to remake Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light so that software from their earlier days could be experienced by more players. This time, they would also appeal to the international market as Marth was a prominent character in Smash Bros., and with the small but steadfast audience in the West after the release of the Blazing Blade, they thought it was important to have the game localized.

The team approached the project not merely as a straightforward remake but as a 'renewal,' aiming to bring the original to a new platform with updated mechanics. Their greatest challenge lied in striking a balance between incorporating fresh elements and preserving the authentic atmosphere of the original version with the original director no longer at the helm.

Kouhei Maeda, Koji Kawasaki, and Toshiyuki Kusakihara were the three wise men responsible for overseeing the story and script which was heavily lifted from FE3. The team opted for minimal additions and chose not to burden players with unnecessary details. Instead, efforts were directed towards streamlining the story content from the original, in stark contrast to the expansions seen in subsequent or previous entries.

The game sold decently well in Japan, although it didn't sell amazing over here in the West. Despite that, it received a generally positive reception, and amongst the fandom, it's one of the few games that are more positively regarded.

Journey to the West

To get this game to the West, however, it needed to be translated, localized, and published. With previous entries, starting with FE7, it was normal for FE games to be localized in-house by Nintendo Treehouse, however with their eleventh entry, Intelligent Systems opted to entrust this localization job to 8-4, Ltd.

The company of 8-4 is stationed in Shibuya, Tokyo, and was founded in 2005 by Hiroko Minamoto and former Electronic Gaming Monthly (EGM) editor John Ricciardi. The first game localized by 8-4 was Mario Tennis: Power Tour and the team has localized a large variety of games including Tales of Vesperia, Tekken 6, and Dragon's Dogma.

Intelligent Systems seemed to be satisfied with 8-4's work with FE11, as they contracted them several other times to work on future Fire Emblem games, such as Fire Emblem: Awakening, Fire Emblem Echoes, and Fire Emblem Three Hopes.

When localizing games, 8-4 usually gets involved in the process midway through a game's development, gaining access to a build of a game and the script. When first gaining access to the game, they tend to familiarize themselves with the game as well as other games in its series by playing through them and taking notes. When actually getting into translating, they use large spreadsheets containing the script in both Japanese and English and work from there.

8-4 cites Richard Honeywood, founder of Square's localization department, as an influence on their translation style. Aside from translating the text, 8-4 attempts to convey the same experience as that of the original language version through attention to tone, user interface, and cultural references. 8-4 also cites Baten Kaitos Origins' localization as one of their favorite projects, as the developers allowed them to take over every aspect of localization including script, debugging, quality assurance, and voice production.

8-4 is still going strong as a company now, providing translation for Masahiro's Sakurai's YouTube series on game creation.

Back on the topic of FE11, despite the PAL version of FE11 releasing before the US version, it was built off of the US version, rather than the other way around. The US version of FE11 was localized by 8-4 in collaboration with Nintendo Treehouse, then the PAL version of the game would use 8-4’s script as a base, and adjust the aspects from there. In fact, most localizations of games for other languages are built off the English versions rather than working directly off the Japanese version.

Because of the nature of this way of adaptation, the PAL version also has certain bug fixes that do not appear in the US version of the game. Apart from that, the PAL version features Commonwealth spellings for terms and phrases, like changing color to colour, or defense to defence.

The US version of FE11 uses the phrase "Another thing coming," which is a common misconception or misinterpretation of the original phrase "Another think coming." Over time, the incorrect version has become widely accepted and used, even though it deviates from the original meaning. While the PAL version opted to use the original saying, the English version instead used the more colloquial phrasing.

The most discussed change between the PAL version and the US version is some of the name changes, like 'Caeda' being referred to as 'Shiida,' or 'Navarre' being referred to as 'Nabarl.' A lot of people incorrectly assume these names originated from older English patches of FE1 or 3, but these names are, in fact, the official ones used in the PAL versions.

A lot of these interpretations actually come from both Super Smash Brothers Melee and Brawl. Some of these names would be used in those games for trophy descriptions and sticker names. In Smash, they seemed to be transliterated without too much context, and the PAL games would use these names for consistency but alter a select few of them only slightly to make them sound better in the setting.

The English version of Brawl uses the transliteration 'Nabaaru,' which was changed to 'Nabarl' in the PAL version.

This trophy description calls the antagonistic nation 'Dolua' here, so it’s assumed that the PAL version's choice of using the name 'Doluna' was derived from this. I also love how this trophy description totally spoils the plot twist that happens in Book 2.

Smash was spoiling FE games before Fire Emblem Heroes made it cool.

After that, in December 2020 the first game, Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light would get a rerelease for the series' 30th anniversary, which included a new localization this one done by Nintendo Treehouse. This localization would stay consistent with 8-4's localization of FE11 by reusing the same names for characters and most of the items, but the two localizations would diverge most notably in the game's dialogue, as FE1's English dialogue appeared a lot less flowery compared to FE11's and is more of a straight translation.

What is Localization?

Now then, reading this you've probably heard me mention the term "localization" maybe once or twice. So I wanted to explain what localization implies. At its most fundamental level, localization means adapting something originally crafted for one target audience to a different target audience. This commonly occurs when transitioning content from one language to another, which causes it to be aligned closely with the field of translation.

When translating media from one language to another, a literal translation can sometimes fail to capture the original impact, tone, or context. There may be sayings or terms that create gaps in understanding. And it's typically the localizer's job to bridge these gaps.

Take for instance the French expression "Sacré Bleu," which is a stereotypical phrase used to convey astonishment, shock, or amazement. It's a substitution for the more religiously charged "Sacré Dieu." Directly translating "Sacré Bleu" to "Sacred Blue" would lose its meaning in English. Thus, effective localization involves finding an equivalent expression that conveys similar emotions. In this case, "Oh my gosh!" serves as a lighter alternative to the commonly used "Oh my God!"

Obviously, though, this isn't a one-size-fits-all change, if the fact that the characters are French is important to the story, you wouldn't need to change it at all. Or if the tone is meant to be more positive, a different expression might be used altogether.

Language is very mutable, and many phrases are open to different interpretations, which leads to certain terms being translated in highly subjective ways, especially when the languages themselves are as different from one another as English and Japanese.

As described by Clyde Mandelin in his Legends of Localizations book on Earthbound, several steps were taken by many localizers to adapt games from one language to another. The initial step revolves around obtaining the literal translation of the original Japanese script, essentially forming the skeleton of the game's text. While direct translations can often suffice, they often risk obscuring the full meaning and nuance of the original work, necessitating clarification and adaptation.

Moving on to the clarification phase, the goal is to extract the intended message from the original Japanese text. This involves dissecting nuances, potential jokes or wordplay, tone, and emotional delivery, and noting them.

Subsequently, the adaptation phase commences, wherein changes or revisions are implemented to ensure the game resonates more naturally with the new target audience. Beyond just making terms make more sense to the new audience, alterations might also occur due to external factors such as company policies, technical constraints, sociopolitical climates, feedback from Japanese fanbases, and other similar elements.

A lot of these localization changes aren't strictly reserved for text however, they also include aspects such as cover art, titles, marketing, voice acting, game mechanics, and supplemental material like game manuals.

Furthermore, different companies have different intentions, policies, and methods of localizing certain content, some for malicious reasons, others out of genuine interest in appealing to their new target audience. This in combination with the general subjectivity of how certain things can be translated has been the basis of fierce debates on the internet for decades.

That said, my personal opinion on localization is mostly divorced from my interest in studying and researching this stuff. I may not like or agree with how some people translate things, like with how many people like to use a localization job as an excuse to promote their own political views, but it's still interesting to learn about what the original Japanese script says, and why a particular change was made. Especially with a lot of the more earnest localization projects that allow me to better compare and contrast both scripts and see specifically how they tried to adapt the original work.

I've always been someone who enjoys reading through hundreds of Wiki articles and scraping the bottom of the barrel for information in regards to how my favorite games changed from region to region. I recall vividly how, as a child, I would eagerly compare the Japanese versions of my favorite games and passively pick up some Japanese terms and phrases through my research.

Aside from just dialogue in these games, some elements that I find the most interesting are the more overlooked aspects. For example, there's the Nintendo Entertainment System. As most people may know, the system was designed to distance itself from the standard video game console. Following the video game market crash of the early 80's, there was a stigma against video games in the market. They feared that if it was branded as such, no one would buy it in the West. The design was modeled after a VCR, and it was referred to as an Entertainment system rather than a game system. However, since this crash was mostly limited to the West, none of this applied to the Japanese Famicom, which the NES was adapted from.

Another example is with certain art styles, as in Japanese, it's common for games such as JRPGs to use anime-styled art to advertise their games in parts like cover art, sometimes commissioning popular manga artists such as Akira Toriyama in the case of Dragon Quest. Unfortunately, in an era where anime wasn't as big in the West as it is now, and the risks involved with potentially putting off potential consumers, a lot of this anime art was replaced with more Western D&D-inspired art style.

Over time, as the Western demographic has slightly adapted, many of these types of changes have also evolved, with adaptations that often align more closely with the Japanese versions. Regardless of one's opinions on these changes—whether they were beneficial, necessary, or otherwise—I find it intriguing that such alterations were even made in the first place.

Japanese Writing Systems

In any case, before talking about the localization of FE11, I feel it is important for you, the reader, to have at least a basic understanding of Japanese as a language. This will not only facilitate clearer explanations but also lay a solid foundation for comprehending various translations and interpretations of specific terms.

First, let's talk about Hiragana. Hiragana is a phonetic lettering system, a syllabary comprising characters representing syllables, and serves as the basic script for native Japanese words. The term itself literally translates to "common" or "plain" -kana. Its primary usage includes grammar particles, verb and adjective endings, and to spell out more complex Kanji characters in a system called "Furigana."

With a few exceptions, each mora is represented by one character, which can be a vowel, like /a/ (あ in hiragana), a consonant followed by a vowel, like /ka/ (か in hiragana), or the singular nasal sonorant /n/ (ん in hiragana). Notably, since the kana characters don't represent single consonants (except for the ん character), they are referred to as syllabic symbols rather than alphabetic letters.

In the table below, you'll find the kana that make up the hiragana writing system.

Next, we have Katakana, which translates to "fragmented kana." Similar to Hiragana, it is another syllabary comprising characters representing syllables, including the five main vowels, a consonant followed by a vowel, or a nasal sonorant. The key distinction lies in the fact that Katakana characters are more angular and sharp in nature, such as the character for /a/ represented as ア in katakana instead of あ.

The most notable difference, however, is its applications. Katakana is primarily used for foreign terms, names, technical or scientific terms, names of plants or animals, and similar contexts. In Fire Emblem, every character has their name written in Katakana, including the traditionally Japanese names found in Fates, such as Ryoma and Sakura. In these games, Hiragana and Kanji are reserved for NPCs (Old Man/おじいさん) or characters whose names are more akin to titles (The Immaculate One/白きもの).

Below, you'll find the kana that make up the Katakana writing system.

Lastly, we have Kanji, which, unlike Hiragana and Katakana, is a logographic system adapted from Chinese characters, and plays a major role in the Japanese writing system. Seriously, you don't know Japanese if you don't know Kanji. There are several thousand Kanji characters, each representing a word or a meaningful part of a word. Kanji is generally used for nouns, stems of adjectives and verbs, and to convey complex or specific meanings.

For example, in Fire Emblem, Marth is often referred to as "Prince Marth." If you wanted to write the word "Prince" in Kanji, you'd use 王子 (pronounced as Ōji). The term consists of the kanji 王 (Ō), referring to a King, Monarch, or Royalty, and 子 (Ko), referring to a child or young person. From this example, you can observe that kanji characters don't follow the same pronunciations in every application. Given the extensive number of characters, a table of every character in the system will not be provided.

Because of the context behind each writing system, the system a particular term is written can play a role in the way certain terms are translated or expressed when brought into English.

A system that is less important for practical use but will be helpful in my explanations of Japanese terms is the romaji system. The term itself comes from the words 'ji,' meaning letters, and 'Roman...' meaning Roman. Romaji pertains to the Romanization of Japanese characters, or in other words, the representation of Japanese sounds using the Latin alphabet. This is especially useful for people who are not familiar with or only have a basic understanding of Japanese scripts.

Romanization is the process of transcribing non-Latin scripts into the Latin alphabet. In the context of Japanese, it involves converting hiragana, katakana, or kanji characters into Roman letters, making it accessible for non-Japanese speakers to read and pronounce.

For example, below, I've provided a table expressing the term 'Inu,' which translates to 'dog' within different systems.

In the context of Fire Emblem, a lot of the characters do have official romanizations, these interpretations are seen in material such as artbooks, certain Japanese promotional merchandise, and sometimes in the credits of the Japanese games. It's important to understand that a lot of these names are straight interpretations or appropriations of the Japanese text without carrying over much of the same context if you aren't a native speaker.

For example, a character that we won't be talking about later on is called (シーザ Shīza) in Japanese, which is officially romanized as Seazar. However, the intention is that it's a Japanese spelling of the Latin name "Caesar".

Dakutens and Handakutens

The next thing I wanted to discuss is the usage of Dakuten and Handakuten. A dakuten, represented with a tenten ( ゙ ) on the top right of a kana, is a diacritic commonly used in Japanese kana syllabaries to signify that the consonant of a syllable should be pronounced voiced.

For instance, the character カ is pronounced as /ka/, but with a dakuten added, it transforms into ガ, and the pronunciation changes to /ga/.

The standard pronunciation changes are as follows:

K゙ → G

S゙ → Z

T゙ → D

H゙ → B

(*One exception is the character "Shi" with a dakuten is sometimes pronounced as "Ji" rather than solely just "Zi")

On the other hand, a handakuten, represented with a maru ( ゜) on the top right of a kana, is another diacritic used with kana for syllables starting with 'h' to indicate that they should instead be pronounced with a 'p' sound.

For instance, ハ is pronounced as /ha/, but with a handakuten, it becomes パ, and the pronunciation shifts to /pa/. The standard changes are as follows:

H゜→ P

In the context of Fire Emblem, especially in older entries, the devs commonly used dakutens and handakutens to modify the pronunciations of weapons or magical tomes, assumingly to make them sound cooler or stand out more. A notable example is Osain's axe from Thracia 776, Vogue, which, when rendered in Japanese, would be spelled out as 'Buuji.' However, instead of using a dakuten to change the Hu sound to a Bu sound, the developers chose to use a handakuten to change the Hu sound to a Pu sound, spelling the name 'Puuji' (プージ) to add a special touch to the weapon. Among the English fanbase, this led to the spelling "Pugi," causing confusion for fan translators for years.

Chiisai Kana, Sokuon, and Chōonpu

Chiisai kana (or small kana), as the name implies, are represented by kana that are smaller than usual, but it's not just for stylistic purposes; they serve a functional role. Small kana like "ya," "yu," and "yo" are used to create compound kana, pronounced as a diphthong, a syllable with two vowels. An example of this is found in the cat sound 'Nya.' If written as にや, it would spell out 'Niya.' To accurately depict 'Nya,' a small 'ya' is utilized, written as にゃ.

Additionally, small versions of a, i, u, e, and o are often used in loanwords to express foreign pronunciations not native to Japanese. A prime example is the title "Fire Emblem" itself. In romaji, "Fire Emblem" would be written as "Faiaa Emuburemu." However, since there is no character for "Fa" in the Katakana table, the character "Fu" is used along with a small "a." Together, they form the compound kana "Fa," completing the title.

On the topic of small things, there is also the small tsu, chiisai tsu, or a sokuon (っ in hiragana, ッ in katakana). Unlike other small kana, this doesn't represent a syllable sound, it instead represents a "clogged sound", which essentially means a double consonant sound for the upcoming kana. It serves multiple purposes in Japanese writing, but the common use is for foreign words or titles.

To illustrate its practical use, consider the number six, which is expressed as "Roku" in romaji and written as ロク in katakana. Now, imagine discussing your favorite rock band with a Japanese person. You wouldn't use "Roku" because that means six. Since 'rock' is spelled with a hard 'C,' you'd say 'Rokku.' To represent the '-kku' sound, a sokuon is added, and it's spelled as ロック.

The last noteworthy element is the dash symbol “ー,” also known as the chōonpu (not to be confused with the Kanji character for one, Ichi). This symbol is primarily utilized to signify a prolonged vowel sound from the preceding kana. It is predominantly used in katakana and sparingly in hiragana. In romaji, the sound is usually denoted by a dash above it (as in ā).

A long 'a' would produce more of an /ah/ sound, a long 'i' would result in an /ee/ sound, 'e' would yield an /eh/ sound, 'u' would bring about an /oo/ sound, and 'o' would create an /oh/ sound.

These elongated vowel sounds are common in katakana because Japanese lacks a direct way to articulate sounds like /ar/ or /or/, as seen in words like 'car' or 'error.' Therefore, long vowels are used to convey such sounds, essentially prompting the pronunciation of 'car' as 'kā' and 'error' as 'erā.'

So his name could realistically be translated in many different ways, such as Pokey,

Pohky, Poki, Porky, etc. Since his connection to pigs wasn’t clear until Mother 3,

his name in Earthbound was rendered as Pokey.

Miscellaneous Differences

Now, one of the most talked-about differences between English and Japanese is the representation of the letters L and R. Even if you don’t know anything about Japanese, you probably know about this, as this is where the term “Engrish” comes from, and it's even joked about in a lot of pop-culture media like South Park.

Not every language uses the same sounds or combination of sounds; for example, Khoisan languages use a variety of clicks that don’t exist in the English language. So, a common challenge is how to write non-English sounds in a way that English speakers can say and learn. Japanese doesn’t have a clear L or R sound but something closer to a blend of L, R, and D.

Many native Japanese speakers can’t even hear the difference between English Ls and Rs, so when Japanese take in a loanword from English, like “Line” (or ライン Rein), for example, and have to render that word back into English, it comes down to a guessing game of whether to use either L or R.

They made the wrong guesses.

Another thing I find interesting is how the letter V is represented in Japanese. Japanese doesn’t have a native way to represent “V” sounds, and depending on the word, either a sound B is used (Like the word 'Victory' being spelled as ビクトリー Bikutori) or a U is used (Like the name 'Volo' being spelled as ウォロー Uoro).

However, in recent times, there has also been the addition of the character ヴ, which is a /u/ with a dakuten, which is also used to represent /vu/ sounds. This can be seen in Sacred Stones, with the villain character Valter (ヴァルター), whose name uses the same character in Japanese. However, this is not very commonly used.

When a term is spelled using a /u/ or a /vu/ the translation for it is usually pretty straightforward, but when a b sound is used, it can lead to a similar guessing game on how it's written in English, just like the usage of L or R.

The name of Samus’ famous Varia Suit, actually comes from

this V and B quirk. In Japanese, the name is バリアスーツ Baria Sūtsu,

and likely meant to be "Barrier Suits," but was misinterpreted as “Varia Suit.”

The next point of discussion is how /th/ is interpreted. As you can surmise, Japanese lacks a native way of rendering /th/ sounds found in words like "Thunder." Depending on the particular word, a multitude of different sounds are used to appropriate this. In the case of the word "Thunder," an /s/ sound is used, hence the pronunciation "Sandā."

In another instance, you have the upgraded thunder tome, known as Thoron, which almost completely disregards the 'h' and is spelled as "Toron" in Japanese.

And with the popular series, Mother, the 'th' in that title is represented with a /z/ sound, and uses a spelling which would be written as "Mazā" in Romaji.

The discussion of Aerith vs Aeris comes from this.

Another noteworthy aspect is that the Japanese language lacks a native /uh/ sound, as seen in terms like 'Firegun,' 'Ulster,' or 'Munster.' The standard Japanese 'u' makes a sound similar to the /oo/ in 'food' or the /u/ in 'rude.' To convey the 'uh' sound, an /a/ sound is used as a substitute.

In the given examples, the pronunciation would be closer to 'Faiagan,' 'Alster,' and 'Manster.' Some astute readers may have also observed that in the preceding section, I spelled 'Thunder' as 'Sandā' and not 'Sundā,' as the same rule applies in that case too.

In Touhou 1, if you take too long in a stage, the game tells you to Harry up

instead of Hurry up.

On their own, all of these differences may seem simple enough. However, many translation challenges arise from the combination of these scenarios, not having a full grasp of the context and meaning, and other general human errors that can lead to mistranslations. For example, in Fire Emblem, you may be familiar with a class called "Lord." In Japanese, this class is spelled as ロード Rōdo, and if you strip away all the context, knowing what we know about Japanese, it's not an easy feat to understand what this is meant to convey.

Transliterating the saying, you have "Rodo," but that's not a word, so you guess again. "Lodo" is also not a word, so you drop the "o" at the end. With that, the term can realistically translate to Rode, Lode, or even Wrode. Similarly, because of the similar pronunciation, it can also be Road or Load. You then remember that a long "o" can be representative of a multitude of different interpretations, and of the ones that make up an actual word, Lord, Lowed, and Rowed are all options.

And just from the term ロード alone, you can extrapolate Rode, Lode, Wrode, Road, Load, Lord, Lowed, and Rowed. It all depends on context to determine which one is representative of the original intention of the writer.

In Breath of Fire 2, there’s an enemy who’s meant to be called LordSlug but got mistranslated as RoadSlug

Another common phenomenon that applies mostly to gaming is space and file size. If you've noticed, in Japanese, you can usually convey more information with fewer characters than you can in English. For example, the mid-game armor knight you recruit, Macellan, is spelled with eight characters in English. Meanwhile, in Japanese, Macellan (called Mishelan in Japanese) is spelled as ミシェラン, using only five characters. And that’s just one character name; it’s not uncommon for the entire script of a game to be two or three times as long in English as it is in Japanese which can cause problems when dealing with limited ROM space.

Fan translations just barely can fit his entire name, and

even then. His name causes issues with other menus with stricter

character limits.

Typically, it's common for localization changes to be made solely to work around the constraints of a game's file size. It was especially common in older games where many terms and phrases would have to be majorly truncated.

The last thing I wish to discuss is Japan’s speech styles. English has various dialects, in the sense that you can distinguish where a person is from based on the way they talk. Japanese is similar to that, but a bit more complex.

One notable thing is the difference between the way men and women speak in Japanese. Not just audibly, but they use different sentence structures, wording, and phrases. If you read Japanese text in a game without looking at any portraits or anything, you can still tell the gender of the speaker.

In addition to gender, the age of the speaker plays a factor in the way they speak, as well as the level of politeness they use. In Japanese classes, they teach you “standard" and "polite” language, but there are many other levels of formality. These typically indicate both one's personality and their relationship to their conversational partner. The tone can range from super polite, to more casual or outright rude.

Lastly, there are dialects, which are easier to understand. Like every other country, the location you grew up in will have effects on how you speak and what word choice you use, and Japanese is no different. Despite being a small country, there are about 20 different kinds of dialects used all over the region. In a fantasy setting like Fire Emblem, dialects are often used to convey a character's archetype based on stereotypes or connotations associated with said dialect. For example, a lot of ruffians and thieves may speak using Kansai-ben.

In localization, all of these factors are considered in writing aspects of a character but can’t be portrayed well enough in a one-to-one translation. In English, we have regional dialects and formal/informal speech, but for a lot of other more nuanced speaking patterns, like gender, age, or the numerous variants of first-person pronouns, some creativity is needed on the part of the localizers to convey the same kinds of tone.

For instance, there are two shopkeepers, one is an old man who sells weapons, and the other is a younger woman selling potions and magic.

I can’t help but notice how much the guy on the left looks like Hardin.

They both effectively say the same things. But, they use slightly different wordings to greet you and welcome you to their shop selection. In the official localization of FE11, this was addressed by giving them certain speech patterns, by making the man sound more formal and professional, while the woman sounds more casual and laid back.

Starting the Game

With that out of the way, let's get right into the real meat and potatoes of analyzing the localization of FE11. I'll start by examining the game's title. In Japanese, the title is ファイアーエムブレム 新・暗黒竜と光の剣, which can be translated as “Fire Emblem: New Dark Dragon and the Sword of Light.” For both of the DS games, they both happen to be remakes, and as such, they introduced the kanji 新 (or "New") to signify their status as remakes. It's not too dissimilar from something like New Super Mario Bros.

Considering the original version was not globally released by the time of this game's launch, the localization likely chose to omit the "New" from the title to prevent potential confusion. Additionally, "Dark" was altered to "Shadow," and the “-and the Sword of Light” portion was omitted, possibly for brevity and simplicity.

The title of this remake is quite straightforward, but things get a little kinky when you add FE1's title to the mix. In Japanese, FE1 is simply called Fire Emblem: Dark Dragon and the Sword of Light (ファイアーエムブレム 暗黒竜と光の剣 lit. Fire Emblem: Ankoku Ryuu to Hikari no Ken). However, Falchion's epithet as it appears in in-game dialogue is spelled "Hikari no Tsurugi," in Hiragana. Meanwhile, as part of the game's subtitle, it's pronounced as Hikari no Ken.

In English, the official name of FE1 was referred to as Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon & the Blade of Light, as of Fire Emblem Heroes version 4.7.0. However, in Super Smash Bros for 3DS and Wii U, the Fire Emblem Fates website, Smash Ultimate, and older versions of Heroes, it was called Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light, using the term "and," rather than an ampersand. In Blazing Blade's official website and in Super Smash Bros Brawl, the name is erroneously referred to as Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragons and the Blade of Light. This is wrong because there is only one Shadow Dragon that appears throughout the entire Archanea Saga.

Additionally, the way that the English word, "Fire" is spelled in this title, and in every other Fire Emblem game's title, deviates from what the standard spelling of "Fire" in Japanese. In Katakana, the title of the games uses the spelling ファイアー (Faiā), while normally the spelling of the word "Fire" is ファイヤー (Faiyā). Furthermore, items like the Fire tome and stuff use this non-standard spelling used in the game's title.

Furthermore, the Japanese spelling of the term Emblem (エムブレム lit. Emuburemu) is also unorthodox. In many English loan words, it's common for /m/ sounds to be swapped out for an /n/ when followed by a consonant. Like in terms such as "Combat," "Hammer," or "Emblem" they would commonly be spelled as "Konbatto," "Hanmā," and "Enburemu." But the spelling of Emblem in the Japanese titles of Fire Emblem ignores this rule and uses /mu/ instead.

The next thing is the difficulty modes present in the game, as most people know there are six difficulty modes. Normal mode, then the following five hard modes. In English, these hard modes have names ranging from Hard, Brutal, Savage, Fiendish to Merciless. However, in Japanese, these modes quite literally are just called Hard Lv1, Hard Lv2, Hard Lv3, Hard Lv4, and Hard Lv5. Which I find pretty funny, considering that most of the Western fanbase uses a similar terminology (i.e. referring to the hard modes as Hard 1 - Hard 5)

Location Names

FE11, along with FE1, 3, and 12, takes place in the continent of Archanea. The Archanean series of games draw significant inspiration from Greek mythology, featuring locations named after locations in Greece. In the Japanese versions, many locations are directly named after their Greek counterparts. In the localized versions, however, the names are tweaked slightly to maintain a connection to the reference while avoiding an exact match.

Initially, I was puzzled about the reasoning behind these changes. However, with some thinking, I believe it's a method to prevent potential immersion breaking for worldwide players. By adjusting the names slightly, the game retains the feeling of a fantasy world loosely inspired by our own, without directly mirroring real-world locations.

Starting off though, we have the continent itself: Archanea. In Japan, Archanea was called アカネイア and romanized as Akaneia. Akaneia is a corruption of the name Acarnania (Ακαρνανία), a region in west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea. In the localization, “Ak-” was changed to “Arch-.” The prefix “Arch-” comes from Latinized Greek and is used to designate something that is first, highest, or high ranking, which is shown in terms such as “Archbishop” or “Archenemy.” Considering Archanea is the pivotal continent of the game, that little change in spelling adds a nice little sense of importance to the nation.

Additionally, the PAL versions of FE11 use the name “Akaneia” as well. However, the PAL version of Fire Emblem: Echoes and subsequent PAL releases would end up using the “Archanea” name instead.

Another interesting fun fact is that in early planning, Archanea was going to be called Altesia アリティシア before the final name was decided.

Also, this is probably more commonly known, but there is an unused Super Smash Brothers Melee stage called “Akaneia.”

And--andandandandand! One last fun fact about Archanea's name is that there's unused text in the title screen of FE1 that romanizes the Japanese name as "Acrnear."

Our next major waypoint is Macedon, the region that all of my favorite characters are from. In Japan, this region was romanized as Macedonia (マケドニア lit. Makedonia). Macedonia (Μακεδονία) refers to an ancient kingdom in Greek antiquity, which was also referred to as Macedon. I assume the name Macedon was chosen over Macedonia in the English versions to make it clear that it was referencing the ancient kingdom that was ruled by Alexander the Great.

Moreover, in the PAL versions of FE11, Macedon underwent a name change to Medon, a contraction of Macedon. This alteration might be attributed to the historical dispute between Greece and the Republic of Macedonia over the name 'Macedonia,' which persisted from 1991 to 2019. Macedon is a region in Greece, but the term 'Macedonians' also referred to Slavic people. Originally not an independent country, Macedon gained independence after the breakup of Yugoslavia.

The people of Greece took issue with Macedonia adopting this name, fearing it would create confusion with the Greek region of Macedonia. Additionally, they felt that the sun flag symbolized the Slavic Macedonians appropriating Greek heritage. As a result, Macedonia had to adopt the temporary name 'Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia' for nearly 30 years. However, in 2019, a treaty with Greece led to the country adopting the name 'North Macedonia.' This agreement facilitated North Macedonia's entry into NATO and potentially the EU in the future.

The next nation is Grust, the homeland of Camus, Lorenz, and the royal kids, Yuliya and Jubelo. In Japanese, this region is romanized as Grunia (グルニア lit. Gurunia), which comes from Gournia (Γουρνιά), a palace complex located on the island of Crete-Greece. The localization change to Grust is one of the bigger departures from the Japanese name. Grust is a commune in the Hautes-Pyrénées department in southwestern France. I'm not sure why they changed the name so much, but if I were to guess, I'd assume it had something to do with the similarities between the nation and France, though that's highly speculative.

Marth’s homeland, Altea is often romanized as Aritia in Japanese (アリティア lit. Aritia). "Aritia" has no real-world equivalent, however, Aritia may just be a corruption of “Altea”, since Altea is the name of a city in Spain. (Ironically, it’s located in the Valencian Community, Valencia being the Japanese name of the main continent in Fire Emblem Gaiden and Echoes, which was renamed Valentia in localization).

It's also worth noting that the name "Altea" was actually first used in Super Smash Brothers Melee.

Another thing worth noting is that the old fan translation of Final Fantasy II referred to the nation of Altair as “Altea.” Another fun fact is the fact that the home planet of Princess Allura from the mecha anime series Voltron is also called “Altea.”

Next is Lefcandith, which was officially romanized as Lefcandy in Japanese (レフカンディ lit. Lefkandi). The name comes from Lefkandi (Λευκαντί), a Greek village on the island of Euboea notable in archaeology.

One of the more interesting names is the Capital of Archanea. The capital goes by different names, sometimes it’s simply referred to as “The Palace”, other times it's the “Millennium Court," and sometimes it's “The Ageless Palace." In Japanese, the location is called (王都パレス) The Royal Capital of Palace. The strange thing is that the term Palace is used as if it's a proper noun, rather than a common noun. The Japanese game would even use the names パレス城 (Palace Castle), or even sometimes パレスの王宮 (The Palace of Palace.)

パレス can be translated as Palace, but it can also be translated as Pales. It would be possible that the term was meant to be based on the Roman deity, Pales, but considering that it was almost always romanized as Palace, makes me believe that's not the case. That said though, the fan translations did use the term “Pales” to describe the capital city.

The next location on our list is Pyrathi, which is romanized as Peraty in Japanese (ペラティ lit. Perati). This name may come from the region of Perati (Περάτη), a small settlement near Livek in the Municipality of Kobarid in the Littoral region of Slovenia. The name "Perati" may also come from Perateia, a small territory of the Trapezuntine Empire located on the Crimean Peninsula. As the rest of the empire was on the other side of the Black Sea, the name Perateia is believed to come from Peraia (περαία, "land across, opposite"), a word indicating an island territory across the sea, which parallels the coastal nature of the in-game nation.

Now, trace a line around the continent's northeastern plains, and you have Aurelis. In Japanese, this region's name was romanized as Orleans (オレルアン lit. Oreruan). Orleans comes from Orléans, a French city located southwest of Paris, the French naming origin is also why the 's' is silent. Orléans is most known as the site of one of the first battles of Jeanne d'Arc. The city of Orléans was originally called Cenabum in ancient times. However, during the 3rd century AD, an emperor named Emperor Aurelian rebuilt this ruined town of Cenabum and renamed it after himself. The new name was “Civitas Aurelianorum” (city of Aurelian). Over time, the name of this city would evolve from Aurelian’s to Orléans. And the name “Aurelis” came from the old name of this city, and the name of the former emperor, Aurelian.

The minor location, Menedy, has the same name in both languages, except with a slightly altered spelling (メニディ lit. Menidi). The name Menidi (Μενίδι) comes from a former municipality in Aetolia-Acarnania, West Greece.

Another minor location is Chiasmir, an island north of Grust. In Japanese, this location is romanized as Cashmere (カシミア lit. Kashimia). If this location isn’t named after the fiber material used to make yarn and wool, it would make me think this location is named after Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent.

Next is Thabes, in Japanese this location is romanized as Thebes (テーベ lit. Tēbe), which references Thebes, (Θῆβαι) a city in Boeotia, Central Greece. This location is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. It can also refer to the location in Egypt, an ancient city along the Nile River. The English name Thabes is merely just a corruption of the name Thebes.

Another location is the Samsooth Mountains, or rather its colloquial name, the Devil’s Mountain. In English, this was changed to Ghoul’s Teeth. I’m not too sure why, but I always much preferred Devil Mountain, it sounds more threatening, and fitting as the location of where you get your first Devil Axe.

The last location that got a more than minor name change was Dolhr, the region of the Manaketes, and the Dragonkin Realm. In Japanese, this location is officially romanized as Durhua (ドルーア lit. Dorūa). I don’t believe Durhua means anything, nor does it have a real-world equivalent. The region was originally translated as Dolua in the English version of Super Smash Brothers Melee, and then the English version of Super Smash Brothers Brawl used the name Doluna. Doluna would be the name that the PAL version of FE11 ended up using, while the US version would use Dolhr.

As far as I know, none of these names have any meaning and are just made-up location names, but it’s a good example of how one term can be rendered in many different ways. While there isn't much else to say, an interesting thing to note is that "Dolluer" is yet another possible interpretation, as it was used in some unused strings of text in FE1.

Weapons

When it comes to weapons and classes, a lot of the localization changes did not originate from FE11 but are carryovers from FE7's localization. That said, I'm still going to cover a lot of these changes since I still feel it's necessary.

Something that I find interesting about weapons in Fire Emblem is that you may notice some of them are written in Katakana while others are written in Hiragana or Kanji. In particular, a lot of the more basic weapons, like an Iron Sword for example is written in Hiragana or Kanji and uses the Japanese words for "Iron" and "Sword." For example, the Iron Sword is called 鉄の剣 (Tetsu no Tsurugi) in Japanese.

However, some of the more special weapons, like a Killer Lance, are written in Katakana, and use a Japanese spelling of the English words for "Killer" and "Lance". For example, the Killer Lance is called キラーランス (Kirā Ransu) in Japanese.

That said, the first specific weapon I want to discuss is the Killing Edge, as that's the first one with a notable name change. In Japan, this weapon is very bluntly referred to as a 'Kill Sword' (キルソード lit. Kirusōdo). The Killing Edge doesn't follow the exact same naming convention as the other high-critical weapons, such as the Killer Lance, Killer Axe, and Killer Bow, and this is the case in both English and Japanese.

My speculation is that they wanted to retain the naming difference between the sword and the other variants, but also wanted a cool sounding name to make the weapon standout in English the same way 'Kill Sword' does in Japanese. Because, as cool as Kill Sword might sound in Japanese, it's a little clunky in English. For example, do you think "Korosu Ken" sounds cool? Well, it is, but it shouldn't. Because in Japanese, it's a lot less impressive as a name.

So their workaround for "Kill Sword" was changing the term 'Kill' to the same word in a different form, 'Killing,' and 'Sword' to another word that could mean sword; in this case, 'Edge'. Making the name sound cool and badass, retaining the different naming convention compared to the other high-critical weapons, and not having to change the name too much.

Also fun fact, there’s a book and a movie both named “The Killing Edge.” It’s not relevant to this discussion, I just thought it was kind of neat.

The next change is with the Thunder Sword (サンダーソード lit. Sandāsōdo) being renamed to Levin Sword. The term 'Levin' is just an archaic English term for 'lightning.' However, what makes this change interesting to me is the context behind it. As you can see, this weapon's name in Japanese uses a Katakana spelling of the English word for 'Thunder.' Normally in Japanese, you wouldn't use the English word 'Thunder' in regular speech unless it was the name of something special like a Western-based series or the name of an attack. In a regular conversation, such as talking about the weather, you'd use 'Ikazuchi' ( いかづち). So rather than translating サンダーソード directly into 'Thunder Sword,' they used a similarly less common word for lightning to represent the sword name, that being Levin.

Another thing I love about this weapon is that this naming theme is consistent amongst multiple games. In FE1, FE3, their respective remakes, Awakening, Fates, and Three Houses, all the games where this weapon is called サンダーソード in Japanese, it is translated as "Levin Sword."

However, in the rest of the games that this sword appears in, like Fire Emblem Echoes or Engage, in Japanese, this weapon uses the name Thunder Sword (いかづちの剣 lit. Ikazuchi no Ken), but using the more standard native terminology which is written in Hiragana. For a native Japanese speaker, this name would be quite a bit more standard, and this is actually echoed in English, as in those particular games, this weapon is translated as the more standard "Lightning Sword," and I love how the English version of these games carry over this distinction.

Next is the Wyrmslayer, which is in a bit of a weird boat. For one, in every Japanese Fire Emblem game, this weapon is called "Dragonkiller" (ドラゴンキラー lit. Doragonkirā), but in FE11 and 12, and only those games, it is instead called "Dragonsword" (ドラゴンソード lit. Doragonsōdo.)

The next thing I wanted to mention is that many of the effective weaponry, specifically the ones that end in '-slayer,' are instead referred to as '-killer' in Japanese. I'm not too sure why this change was made. Over time, I've grown to prefer the suffix '-killer.' Since '-slayer' is a common suffix used in many fantasy weapon names in other series, the term -killer gives these Fire Emblem weapons their own unique identity.

The last note is that, while I'll talk a bit more about dragons later on, a Wyrm refers to a type of dragon characterized by being limbless and wingless, almost like a serpent or snake-like creature. I'm not sure why they would change "Dragon" to "Wyrm" in this case, but if I were to guess a reason, I'd assume it was just because of space.

Now, let's talk about lances, but before that, I have some things to mention about the weapon type. You may notice that in Japanese, many of the standard lances are denoted using the Kanji 槍 (yari), which... isn't what I would personally call a one-to-one translation of "lance."

The Yari refers to a traditional Japanese blade (日本刀 lit. Nihontō) which is fashioned into the shape of a spear, particularly characterized by its straight-headed design. The yari has a rich history dating back to feudal Japan. Originally developed during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), the yari quickly became a staple weapon for foot soldiers and samurai alike.

Its design evolved over time, with variations emerging to suit different combat scenarios. As warfare transitioned from open-field battles to more confined spaces, such as castle sieges and indoor skirmishes, the yari remained a versatile and effective weapon. Throughout Japan's history, the yari continued to be used by various warrior classes and played a significant role in shaping military tactics and strategies. Even in modern times, the yari maintains its cultural significance and is still practiced as part of traditional martial arts like sōjutsu.

I bring this up because, in contrast, the lance gained prominence as a primary weapon for mounted warriors, and knights during the Middle Ages. It played a crucial role in the development of chivalric warfare and the tactics of cavalry charges. Lances were typically made of wood, often reinforced with metal tips or heads, and were wielded by riders on horseback during battles and tournaments. As warfare evolved and firearms became more prevalent, the use of lances on the battlefield declined, although they continued to be used ceremonially in cavalry units.

Now, due to the differing use cases and general designs of these two types of weapons, I believe that "Lance" isn't a very accurate translation for "Yari" in this context. I've always felt that "Spear" would be a much better translation for "Yari." Among all the weapons labeled as "Lances" in the English games, only a select few resemble actual lances, and these weapons are never exclusive to mounted classes.

That being said, this issue is actually addressed in some of the later Kaga games like Berwick Saga, where Yari (Spears) and Lances are actually classified as separate types of weapons, with the latter being exclusive to mounted classes.

With that out of the way, the first 'lance' I wish to discuss is the Javelin, which in Japan is simply referred to as "Hand Spear" (手槍 lit. Te Yari). This actually matches with the Japanese name of the Hand Axe (Te Ono), but I can understand how "Javelin" would get the same point across.

The next weapon we have is the Ridersbane, which was referred to as the Knight Killer (ナイトキラー lit. Naitokirā) in Japanese. I believe this was changed to make it more clear that it's effective against classes that ride horses, not specifically knights since the Armor Knight class is also called a "Knight."

Similar to the Levin Sword, the Ridersbane has also gone through multiple different names. In English, it's also been called Horseslayer and...Knight Killer. While in Japanese, in addition to Knight Killer, it's also been dubbed Horse Killer (ホースキラー lit. Hōsukirā).

The last lance to receive a different name was the Dragonpike, which was originally called Dragonlance (ドラゴンランス lit. Doragonransu).

Now, I will be skipping quite ahead because none of the axes or bows received any notable changes to mention in depth. A lot of them are translated directly.

That said, the ballistae featured have received more significant changes, starting with Arrowspate. In Japanese, this weapon is called Quincrane (クインクレイン lit. Kuinkurein). To explain the Japanese name a bit, the term Quincrane is an anagram of the word “Cranequin”, which is a mechanical device used to arm a crossbow.

A lot of older fan translations would misinterpret the Japanese name, and render it as “Quick Rain”, which is kinda funny. Arrowspate comes from “Arrow..." obviously, and “Spate,” a term that refers to a large number of similar things or events occurring in quick succession. Since rain describes water droplets that fall from the sky in quick succession, in the loosest sense of the word, "Quick Rain" may not be so farfetched.

Next is Stonehoist, which is called Stonehedge (ストンヘッジ lit. Sutonhejji) in Japanese. “Stonehedge” might be referencing Stonehenge, a famous ancient monument located in Wiltshire, England. Stonehoist on the other hand is a bit self-explanatory. It’s a big stone that’s being hoisted up in the air to hit the enemy.

The next weapon is Hoistflamme. In Japanese, this artillery is called Firegun. I can see why “hoist'' was used instead of “gun” since it makes it more clear that this is a ballistic catapult weapon. And flamme is just French for fire. Fun fact though, the Japanese version of FE1 and FE3/11 use different spellings for “Firegun''. FE1 uses Faiyagan (ファイヤーガン), while FE3/11 uses Faiagan (ファイアーガン).

The last notable ballistae is Pachyderm, which was originally called Elephant (エレファント lit. Erefanto) in Japanese. An Elephant is a heavy plant-eating mammal with a prehensile trunk, long curved ivory tusks, and large ears, native to Africa and southern Asia. It is also the largest living land animal alive.

Meanwhile, a pachyderm is a general term used to describe thick-skinned land mammals such as elephants and rhinoceroses. I’m not sure what the rationale behind this weapon's name is; I’ve heard it was named after an Elephant gun, which is a rifle gun, and other sources have said it’s because the weapon looks like an elephant in FE1.

An interesting fact however is the fact that in Japanese, the term Elephant was reused in Fire Emblem Echoes for a class that would be renamed to "Oliphanter" in English.

The dragon stones that appear in the game, more or less have one-to-one translations, the only differences being stuff like Fire Dragon Stone (火竜石 lit. Karyūseki) being shortened to just "Firestone" to save space, which applies to all the dragon stones.

Regarding the magical tomes, the first change of note is Swarm, which was called Worm (ウォーム lit. Wōmu) in Japanese. The spell is a swarm of bees or wasps being summoned to attack the enemy, so I believe Swarm would make more sense in that context. Though the name "Worm" was retained in Radiant Dawn.

The next change I wanted to mention is Blizzard. In the Japanese versions of FE1, 3, 11, 12, and 3H, this tome is spelled “Blizzar” (ブリザー lit. Burizā), while in every other game, it’s spelled “Blizzard” ( ブリザード lit. Burizādo). Interestingly, in the games that use the full name ブリザード, the tome appears as a long-ranged tome, so I assume this was to signify that these are different tomes. Unfortunately, this is lost in translation.

The most interesting tome I wanted to mention is Bolganone, which, at first glance, just looks like a made-up word. This localized name originated from Fire Emblem: Path of Radiance and is a direct translation of the Japanese name Boruganon (ボルガノン).

However, a theory I heard is that the name may be derived from the term "Vulcan" + "on." Vulcan is the Roman god of fire, volcanoes, deserts, and metalworking. This would actually align with how Thoron is named after Thor, the Norse god of thunder, strength, and protection of humankind.

Additionally, the spelling of Vulcan (バルカン lit. Barukan) is altered into the term Volgan (ボルガン lit. Borugan) by changing the /u/ to an /o/ and using a dakuten to change the /ka/ into a /ga/ for added flair, similar to what I mentioned earlier with the Pugi axe. The English version took this one step further by interpreting the V as a B.

This also parallels how, in Japanese, Thoron exhibits a similar corruptive property, as "Thoron" is spelled as トロン (Toron), whereas the spelling of the name "Thor" would be トール (Tōru).

Finally, in Boruganon (ボルガノン), the suffix "-on" is added at the end, possibly to signify it as the highest level fire magic. Thoron similarly has "-on" at the end, marking it as the highest level thunder magic. This is somewhat akin to how "El-" is added as a prefix to mid-level anima tomes.

While I’m at it, I’ll also mention that in FE3, tomes were followed by the suffix “の書“ (no sho) which translates to “Book” or “Tome”. So, whereas in most games, Fire is simply called “Fire”, in FE3, it would be called “Fire Tome”.

Staves and healing items are actually a bit more interesting from a translation standpoint. First, we have Heal, which is called Live in Japanese (ライブ lit. Raibu). My assumption is that “Live” refers to “Alive” or “Life” in the sense that you’re keeping someone alive, or adding to their life force by healing them. This was changed to "Heal” in localization as it conveys the same meaning, but “Heal” is more standardized in RPGs. Fun fact though, the Renewal skill in FE4 and 5 is also called “Live” in Japanese.

Next is Mend, which was romanized as Relive (リライブ lit. Riraibu) in Japanese. “Relive” just means to live through an experience again, however, I don’t think this was the actual intent behind the name. In addition, I've seen older fan translations of FE1 render the name of this staff as “Relieve”, which makes sense as a staff name, but was likely not the original intention either.

In any case, with Mend and the next few staves, I want to do a bit of an interactive exercise, so as I discuss the next few staves, I want you to take out a pen and pencil and see if you notice a pattern with the Japanese names.

The next staff is Recover (リカバー lit. Rikabā), which is the same in both languages, so I’ll skip that and talk about Physic, which in Japanese, was romanized as Reblow (リブロー lit. Riburō) (which is sometimes fan translated as Libro), an odd name for a staff that can heal from far away with no apparent Japanese meaning.

Then we have Fortify, which is called Reserve (リザーブ lit. Rizābu) in Japanese. I think it can be assumed that "Reserve" refers to a reserved, closed-off, and protective person, which “Fortify” is probably meant to reference, as fortifying your army means that they are being protected.

Now, after hearing these four Japanese names of the staves, I want you to see if you've noticed the pattern I alluded to before. So, with the Japanese names of Mend, Recover, Physic, and Fortify, what do the Japanese names all have in common? (Take your time)

A.) They all end with a chōonpu

B.) They all begin with the リ kana

C.) They all have multiple Japanese meanings

D.) They all were completely renamed in English

Okay so, if you selected the second option, you were correct, every high-level staff begins with the リ (Ri) kana in Japanese. In fact, the tome called Nosferatu, which heals the caster upon attacking the enemy, is called “Resire,” (リザイア lit. Rizaia) which also uses the same Ri- prefix. I assume it would be hard to carry these same patterns in English, while also making all these names make sense in English, which is unfortunate.

Buuut, if I were to think of a way to retain this pattern, I’d probably rename Mend to “Relieve,” Physic to “Remedy,” Fortify to something like “Reinforce,” and either call Nosferatu “Respite” or keep it as "Resile." The French version already uses “Remedy” (Remède) for Physic, and the German version already uses “Reinforce” (Stärkung) for Fortify as well, so it's probably not impossible to retain this pattern, and the FE7 localizers were probably just being lazy.

The last staff to note is the Barrier staff, which was originally called Magic Shield in Japanese—often shortened as M・シールド (M. Shield). In most languages, this staff is still called “Magic Shield”, like in German, Italian, and Dutch. It’s actually only called Barrier in English and French (where it's translated as Bouclier), which is interesting. I always assumed it was changed just for space, but other languages have no qualms with abbreviating the word "Magic."

Items

For the items, there aren't too many items I want to talk about. In fact, a lot of the items I want to reference are their FE1 iterations.

The first item I want to talk about is the Pure Water, which in Japanese was called Holy Water (聖水 lit. Seisui), which was likely changed due to the religious connotations. There's not really much else to say about that.

With a lot of the stat boosters, any changes the English version received come down to semantic changes to either save space or sound smoother. These changes are Power Drop (力のしずく) -> Energy Drop, Spirit Powder (精霊の粉) -> Spirit Dust, Dragon Shield (竜の盾) -> Dracoshield, Member Card (メンバーカード) -> VIP Card, Master Proof (マスタープルフ) -> Master Seal, and Empyreal Whip (天空のムチ) -> Elysian Whip.

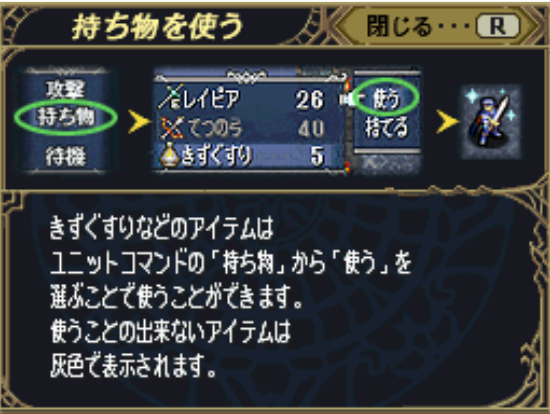

One stat booster I want to mention, though, is the Arms Scroll. In FE11 and the Tellius games, this item is called Arms Scroll, which in Japanese is referred to as the Technique Book (術書 lit. Jutsu Book) and romanized as "Manual." However, in FE1 and FE3, this item is called Manual in both English and Japanese (マニュアル lit. Manyuaru). I wanted to mention this because I feel the usage of Kanji and Katakana in the respective names does a good job of making it clear that these are two different items, and the localizations of these two items make sense. As the Manual boosts Weapon Level while the Arms Scroll boosts Weapon Rank.

In the same vein, FE1's 2020 localization renamed a couple of the items. Like the Knight's Crest (きしくんしょう) being renamed to Paladin's Honor, Dragon's Whip (ひりゅうのむち) being renamed to Skydrake Whip, and Thief's Key (とうぞくのカギ) being renamed to Master Key.

With the case of Paladin's Honor, because of the fact that Armor Knights can't promote in FE1, it specifically mentioned Paladins to make it more clear that only Cavaliers can use it to promote to Paladins. And with the Skydrake Whip, it's arguably more accurate than the common translation "Dragon Whip" since in ひりゅうのむち (lit. Hiryuu no Muchi), "Hiryuu" refers specifically to a flying dragon, hence "Skydrake."

However, the Master Key is a change I take issue with. In every prior game, the Thief's Key (とうぞくのカギ lit. Touzoku no Kagi) has always been localized as "Lockpick." In fact, in my fan translation of FE1, I used the name "Lockpick." But in FE1's localization, they chose to instead rename this item to "Master Key" as a way to tie it in with a separate item in FE11 also called the Master Key (万能カギ lit. Bannōkagi)

This change rustles my jammies because anyone who has played FE11 and used the Master Key will be confused when they see the "same" item in FE1, only to realize it's a completely different item only usable by thieves. I feel it causes unnecessary confusion and it isn't even accurate to the Japanese version.

Anyways, the rest of the items I want to mention are the Multiplayer Cards available in the PvP mode of FE11. There are many cards named after stats or particular skills. The only change I want to mention is that in Japanese, they use the suffix "no gofu" (の護符) which just translates to "protective charm." This suffix was dropped in English presumably for space.

Regalia and Holy Items

Concluding the items section, let's discuss the regalia weapons. First is Mercurius, the holy sword bestowed upon you by Est in Book 1 and wielded by Astram in Book 2. In Japanese, this sword is commonly romanized as Mercury (メリクル lit. Merikuru). However, the spelling Merikuru can be interpreted as something like Mericle, which is often misinterpreted as "Miracle." Hence why older fan translations often referred to this weapon as the "Miracle Sword."

Additionally, in FE1 dialogue, it bears a longer name, Mercury Rapier (メリクルレイピア lit. Merikuru Reipia). This perhaps explains why it's a Prf for Marth in that game, since this title presents it as a stronger Rapier, and the weapon icons in later games even match this.

The term "Mercury" is the common anglicized form of the term "Mercurius." Mercurius is a Latin term referring to the Roman god Mercury, the messenger of the gods in Roman mythology, and also representing the planet Mercury in astrology.

In addition, St. Mercurius was the name of a Greek soldier, who became a Christian saint and martyr. They are known in Arabic by the name Abu-Sayfain (أبو سيفين), which means "father of two swords." This is fitting since, in FE12 H4, the wielder of the Mercurius can also be seen as a martyr because he can be sacrificed and killed easily by generic thieves upon joining in order to give you the Mercurius.

As I said, the katakana spelling doesn’t exactly read as "Mercury," and instead appears more as a corruption of the Japanese rendering of Mercurius (メルクリウス lit. Merukuriusu), but with the last two kana omitted and ル /ru/ and リ /ri/ being swapped.

The next weapon is the holy spear, Gradivus, used by the two men who would be stuck in the Gordian knot of Nyna’s heart, Camus in FE11, and Hardin in FE12. In Japanese, this lance is romanized as Gladius (グラディウス lit. Guradiusu). The term Gladius comes from... gladius, the type of simple sword used by Roman Soldiers. However, it can also just be a Japanese way to spell Gradivus, as I stated before, it's common for /u/ sounds to be used to represent a /vu/ sound.

The term “Gradivus” itself comes from Mars Gradivus. In Classic Roman religion, Mars would be invoked under several titles, one of which being Mars Gradivus, a Roman god by whom a general or soldier would swear an oath before a battle.

Another important weapon, or rather staff, is the staff that was originally a Prf to Elice, Aum. In Japanese, this was called Om (オム lit. Omu). Om is a sacred sound, syllable, mantra, or invocation in Hinduism. And “Aum” is just an alternate spelling of Om.

The last weapon is Imhullu, in Japan, this was romanized as Mafu (マフー lit. Mafū), which is often fan-translated as Maph. The term is a Katakana spelling of the kanji 魔風, “demonic wind.” Meanwhile, Imhullu comes from the now-extinct Akkadian, “imhullu,” one of the seven winds summoned by Marduk to slay Tiamat in the Babylonian creation myth Enūma Eliš. Mafū wouldn’t really invoke any of the same feelings in an English audience, so instead of just straight translating it as “Evil Wind”, they went with the ancient Babylonian reference. While Imhullu probably still doesn’t have any real relevance to an English speaker, it does sound a lot more like a spell that an old evil wizard would use than Maph does, which just sounds like “Math.” And while math is equally as scary of a concept, I prefer Imhullu.

Classes

Next, we have classes. The first thing I want to discuss is Dragon Knight (ドラゴンナイト lit. Doragon Naito) being changed to Dracoknight in English. This itself isn’t really a big change, but up until Radiant Dawn, this class has always been called “Wyvern Rider.” Which, to me, isn't a good localization at all. Wyverns refer to a specific type of dragon that is characterized by only having two legs, a more slick arrow-like skeletal structure, and swift movements while flying.

The "Wyvern" Riders that appear in the GBA games clearly have four legs and features reminiscent of a general dragon. In addition, in FE8, they introduced the Wyvern Knight class, which features the unit riding an actual wyvern, and the design is notably different from that of the Wyvern Rider or Wyvern Lord classes.

I personally feel that since "Dragon Knight" or even "Dracoknight" refers to general dragons and not a specific type of dragon, that name would make perfect sense to use as a class name rather than renaming them to Wyverns when they aren't actually Wyverns.

On the left is a Wyvern, notice the lack of front legs, and on the right is a dragon, notice the broader-looking body structure.

However, I think the main reason why FE7 renamed Dragon Knight and Dragon Master to Wyvern Rider and Wyvern Lord respectively is to differentiate these dragons from the feral dragons that were fought in The Scouring in the Elibe games, then later games just continued this naming convention until Radiant Dawn opted to change it. In any case, the dragons that these units ride in both FE1 and FE3 do resemble actual Wyverns, so FE1's insistence to refer to this class as Wyvern Knight makes sense.

Another change is Social Knight (ソシアルナイト lit. Soshiaru Naito) being changed to Cavalier. According to an interview discussing the release of FE6, one of the devs explains that “A social knight is a term that refers to a knight who has a master to serve.” While a bit vague, my understanding is that “Social” in this context means to refer to a society or a community, similar to how it’s used in phrases like “Social Security” or “Social Services.” This means that Social Knights are knights who fight for a community, which is one of the primary codes of chivalry. Cavalier likely makes more sense to an English speaker, but strips away some of the uniqueness established by the Japanese devs.

Speaking of knights, one minor change is Armor Knight → Knight. I assume this change was made because specifying “Armor” would have been redundant since “Social Knight” was renamed to Cavalier, and there were "no other knight classes." I’m not a big fan of making the class name less specific, especially in FE9 where these classes got variants and the mounted classes were called “Sword Knight”, and “Lance Knight.” Nonetheless, I find it funny how English speakers still refer to Knight as “Armor Knight” anyway. Eventually, Fire Emblem Three Houses used the name "Armored Knight" in its localization, so that it would be more consistent with the Japanese class name.

Additionally, something I wanted to briefly mention is the General class. In Japanese, the General class has always been a transliteration of the English word General (ジェネラル), written in Katakana. This is the case for every game except for FE1, where instead the class uses the Japanese term Shōgun (しょうぐん), written in Hiragana.

The next class is Myrmidon. “Myrmidon” is what the legendary warrior people of ancient Greece were called, and because of the general Greek theming of Archanea, this class name fits. In most Japanese games, this class is simply called Swordfighter (剣士 lit. Kenshi), but in the Japanese versions of FE6, FE7, and FE13, this class was romanized as Myrmidon. This was actually because of the fact that these units hailed from Sacae, and were modeled after the various nomadic peoples native to the Eurasian Steppe region.

Real-world Myrmidons were believed to be one and the same as the Bulgars, a collection of Asian steppe nomads whose names were given to the capital of Sacae. And ever since the name was used in FE7's English release, 剣士 was always translated as "Myrmidon" regardless of what future Japanese romanizations used.

Now there are Priests (僧侶 lit. Sōryo) and Sisters (シスター lit. Shisutā), which are called Curates and Clerics in English. There isn’t much to mention, however. “Cleric” is a more common term in traditional RPG games, so I assume it was changed to be more familiar. In addition, “Sister” has a more religious connotation.

On the topic of Curates, FE1, and FE11 are the only English FE games that use “Curate” instead of “Priest”, a “Curate” refers to a clergy member in certain Christian denominations, often an assistant to a parish priest, so I guess they wanted to make it clear that this was a low ranking class... or something.

Next is Ballistician, they are called Ballisticians because they use and operate ballistae. In Japanese, they are bluntly called Shooters (シューター lit. Shūtā), because they shoot projectiles. I kind of prefer Ballistician, in the context of FE11, though in FE1, where they are tanks that shoot stuff from two tiles away, "Shooter" would make more sense. However, because I live in the US, the term "Shooter" has a very different connotation.

Next is the Manakete class, which is Mamkute (マムクート lit. Mamukūto) in Japanese. Fun fact, unused text in FE7 renders the name “Mamkoot” for the use screen of the Flametongue item. Anyway, I'm not sure why this class was renamed. Though, I personally prefer Manakete.

There’s a theory that this line was added in localization to

make the pronunciation of the Manakete class clearer.

The last class is Xane’s personal class, Freelancer. Freelancer comes from the concept of freelance employment, in reference to the fact that Xane can change his “job” or class temporarily by transforming into another unit. In Japanese, this class is romanized as Command (コマンド lit. Komando), which can simply just be the English word "Command," as in a directive to perform a specific task, which in this case is transforming into somebody else.